Film criticism seems too often to live in a world of absolutes. This or that actor is “the voice of a generation.” This or that film “changed movies forever.” Film trends are too fluid and too global to sustain such arguments, I think.

Let’s, just for the sake of argument, believe that Marlon Brando was the cinematic voice of a generation. Was he, then, still speaking for that generation when he made “The Formula” or “Superman” or “The Score” later in his life? Does one still speak for a generation long after one has passed into middle age? Is Sean Penn still the voice of his generation?

This is an appellation that only seems appropriate when young.

So it is with Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless”, now 50 years old, safely ensconced in middle age. It is no longer young. Is it still speaking for its generation? Is it still the movie that “changed film forever?”

If this is so, one would be hardpressed to find its influence -- or Godard’s, for that matter -- anywhere you looked today. Films today are almost exclusively devoid of politics -- real political talk, that is. And film geeks today will kill you if you make a mistake in continuity. You’ll get trashed for that. So how could Godard’s contempt for any kind of coherence be seen as influential?

“Breathless” doesn’t seem to have resonated much even with the people who made it.

Godard, for his part, has apparently disowned the movie, or at least dismissed it.

The other names directly associated with “Breathless” -- which include Francois Truffaut, Claude Chabrol and Jean-Pierre Melville -- all experienced mainstream success. Both Chabrol and Truffaut, of course, are considered classicist in their own way. (Melville died in the early 1970s.)

So, really, how much influence did “Breathless” have on them? Not too much, it seems.

Roger Ebert wrote about “Breathless” in 2003 by saying that “modern movies begin here.” Oh, man. This is the kind of hyperbole that almost never lives up to its premise. How would you even prove this? Godard’s dedication to Monogram Studios, makers of tough little westerns and film noirs (and the Bowery Boys series), tells you right there that there were precursors to his effort.

Roger Ebert wrote about “Breathless” in 2003 by saying that “modern movies begin here.” Oh, man. This is the kind of hyperbole that almost never lives up to its premise. How would you even prove this? Godard’s dedication to Monogram Studios, makers of tough little westerns and film noirs (and the Bowery Boys series), tells you right there that there were precursors to his effort. Why not just say that Edgar G. Ulmer’s “Detour” from 1945 is actually the beginning of modern film? This wasn’t made by Monogram, but what the hell.

For my part, if you’re going to pick the most influential movie made in 1960, I’d name another freewheeling flick, “Psycho”, that has had more lasting influence. Slasher films, sociopaths who live next door, the lonely hotel, the killing of a leading character early in the movie, psycho-sexual confusion, gothic overtones - all of these have had a far, far more lasting effect on movies than “Breathless” will ever have.

And I don’t think that the characters played by “Pacino, Beatty, Nicholson, Penn,” -- the list that Ebert offers - were directly influenced only by Belmondo. Does that mean Bogart, Cagney, James Dean and countless others should be ignored?

And, really, while filmmakers themselves may have admired Godard’s bravado, his intellectualism, and his fearlessness, I think the majority of his acolytes were probably more influenced by his success than anything else. As contradictory as that sounds, I think its true.

Godard essentially stopped making movies with any linear narrative in 1967, when he made “Weekend”, and even then quite a bit of that film is polemics. I like “Weekend.” I like “Breathless”, but I’m not quite convinced of its real value.

I think Godard was too loose, too contemptuous of film technique and too political to have any lasting influence on film. He’s historic, no question, but I think that’s because he has had far more influence on film criticism than he has on film making.

It seems to me the film review offered up by “Variety”, printed on Jan. 1, 1960 got it about right. It doesn’t make too much of the film, but admires what it does best, including the film’s most lasting contribution: its editing style. That much I’ll give the film; it did influence editing techniques for mainstream films.

The review is brief, so we can reprint the whole thing here:

“This film, a first pic by a film critic, shows the immediate influence of Yank actioners and socio-psycho thrillers but has its own personal style.

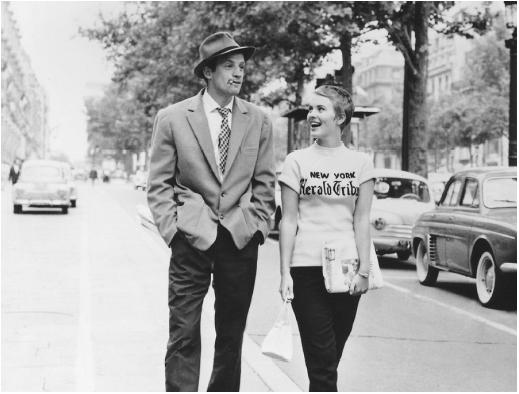

“All of this adds up to a production resembling such pix as Gun Crazy, They Live by Night and Rebel without a Cause. But it has local touches in its candor, lurid lingo, frank love scenes, and general tale of a young childish hoodlum (Jean-Paul Belmondo) whose love for a boyish looking, semi-intellectual American girl (Jean Seberg) is his undoing.

“Pic uses a peremptory cutting style that looks like a series of jump cuts. Characters suddenly shift around rooms, have different bits of clothing on within two shots, etc. But all this seems acceptable, for this unorthodox film [from an original screen story by Francois Truffaut] moves quickly and ruthlessly.

“The young, mythomaniacal crook is forever stealing autos, but the slaying of a cop puts the law on his trail. The girl finally gives him up because she feels she does not really love him, and also she wants her independence.

“There are too many epigrams and a bit too much palaver in all this. However, it is picaresque and has enough insight to keep it from being an out-and-out melodramatic quickie.

“Seberg lacks emotive projection but it helps in her role of a dreamy little Yank abroad playing at life. Her boyish prettiness is real help. Belmondo is excellent as the cocky hoodlum.”