Tuesday, June 29, 2010

It's Time For Movie Critics To Expand Use Of The Word Dystopia

By Lars Trodson

Why is the word "dystopian" always used to describe the future? It isn't really in the definition of the word, but movie critics have adopted it as a kind of shorthand to describe a future that is a mess.

Every movie and every book depicting our supposed future is now described as "dystopian." How many times have you seen this yourself?

Google the phrase "dystopian movies" and you'll get reams of responses — entire sites dedicated to the "Top 50 Dystopian Movies" and on and on and on. But every movie they mention takes place in the future.

A writer on the blog Popcrunch got it right when he wrote: "Pretty much every film in which the future is shitty is considered dystopian, so that means everything from post-apocalyptic to corporate control to biological viruses. It’s a huge field..."

It also seems to be used when a critic wants to describe a future world without beauty.

Labels:

A Clockwork Orange,

Adam Sandler,

Grown Ups,

Jonah Hex,

Lars Trodson,

Metropolis

Friday, June 25, 2010

Why Does Clay from 'Less Than Zero' Want To Remake Our Movie?

Bret Easton Ellis has a new novel out -- it was published on June 15.

In the book, which as another Elvis Costello inspired title, "Imperial Bedrooms", Ellis revisits the characters he created in "Less Than Zero", his famous debut novel from 1985.

The protagonist in both books is Clay (played by Andrew McCarthy in the film version, if you recall), and in "Imperial Bedrooms" Clay has grown up to be a successful writer. He's in Hollywood to help cast a film called "The Listeners."

But, hey, we already made "The Listeners" back in 2005! Somebody should have told that to Bret before he wrote his book. Our version stars Kristan Raymond Curtis, Tim Robinson and Bernie Tato. We have no idea who Clay intends to cast, but we hear he's looking at Selma Gomez and Justin Bieber.

Oy.

See our own little "The Listeners" here on the site.

-- LT

Monday, June 21, 2010

Welcome To The Portsmouth Museum of Art

By Lars Trodson

By Lars TrodsonCathy Sununu, the director of the Portsmouth Museum of Art, has a neat analogy about her vision for the space that opened just over a year ago in Harbour Place.

There was a time when Portsmouth was very much a working port, Sununu said, and ships from all over the world docked here. The city’s streets were inhabited by people of every ethnicity and background, and they brought with them the latest European and Asian fashions.

The now-historic homes lining Portsmouth’s streets were filled with the very latest creations, both aesthetic and industrial. Portsmouth in the 1700s was very much a modern city, showing off wares that had never been seen anyplace in America before.

And so it is with the Portsmouth Museum of Art. “I’d like to be the place where new art gets seen first,” Sununu said. “We’re going to plug into the great new and emerging work that’s happening in New York and Beijing and every place else and bring it into Portsmouth.”

She added that "we're focused on 21st century art, on contemporary, living, working artists."

Friday, June 11, 2010

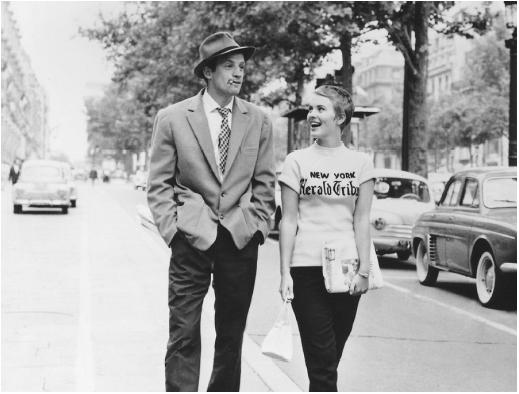

Is 'Breathless' Really That Important?

By Lars Trodson

Film criticism seems too often to live in a world of absolutes. This or that actor is “the voice of a generation.” This or that film “changed movies forever.” Film trends are too fluid and too global to sustain such arguments, I think.

Let’s, just for the sake of argument, believe that Marlon Brando was the cinematic voice of a generation. Was he, then, still speaking for that generation when he made “The Formula” or “Superman” or “The Score” later in his life? Does one still speak for a generation long after one has passed into middle age? Is Sean Penn still the voice of his generation?

This is an appellation that only seems appropriate when young.

So it is with Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless”, now 50 years old, safely ensconced in middle age. It is no longer young. Is it still speaking for its generation? Is it still the movie that “changed film forever?”

If this is so, one would be hardpressed to find its influence -- or Godard’s, for that matter -- anywhere you looked today. Films today are almost exclusively devoid of politics -- real political talk, that is. And film geeks today will kill you if you make a mistake in continuity. You’ll get trashed for that. So how could Godard’s contempt for any kind of coherence be seen as influential?

Film criticism seems too often to live in a world of absolutes. This or that actor is “the voice of a generation.” This or that film “changed movies forever.” Film trends are too fluid and too global to sustain such arguments, I think.

Let’s, just for the sake of argument, believe that Marlon Brando was the cinematic voice of a generation. Was he, then, still speaking for that generation when he made “The Formula” or “Superman” or “The Score” later in his life? Does one still speak for a generation long after one has passed into middle age? Is Sean Penn still the voice of his generation?

This is an appellation that only seems appropriate when young.

So it is with Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless”, now 50 years old, safely ensconced in middle age. It is no longer young. Is it still speaking for its generation? Is it still the movie that “changed film forever?”

If this is so, one would be hardpressed to find its influence -- or Godard’s, for that matter -- anywhere you looked today. Films today are almost exclusively devoid of politics -- real political talk, that is. And film geeks today will kill you if you make a mistake in continuity. You’ll get trashed for that. So how could Godard’s contempt for any kind of coherence be seen as influential?

Tuesday, June 8, 2010

Film Director Joseph Strick, Interpreter of James Joyce And Others, Dies At 86

(From the New York Times) Joseph Strick, an Academy Award-winning director, screenwriter and producer known for filming the unfilmable — in particular weighty, bawdy literary works whose screen adaptations often ran afoul of censors worldwide — died on June 1 in Paris. He was 86 and had made his home in Paris since the 1970s.

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/08/arts/08strick.html?hpw

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/08/arts/08strick.html?hpw

Saturday, June 5, 2010

'Splice'

By Lars Trodson

The most driving question behind the new horror flick “Splice” is this: Would two rock-star bio-scientists that have appeared on the cover of “Wired” drive around in a bright orange Gremlin with racing stripes?

I don’t think there’s a logical answer to that, but then again there is very little about “Splice” that makes any sense. The movie is such a bundle of contradictory emotions -- none of which are handled well -- that the audience is left confused and ultimately defeated. At two key moments in the film the audience did not react with horror or shock but with laughter. What does that tell you?

The movie itself is a mutant; a kind of genetic splicing of “Rosemary’s Baby” and David Cronenberg’s “The Fly.” In fact, this film owes a lot to Cronenberg. It has the flat, cheerless, angular feel of so many of Cronenberg’s early films. (“Splice” was shot in Canada). But that’s not really a compliment. So what is happening here? Clive (a seriously floundering Adrien Brody) and Sarah Polley (much more focused than the material given to her) are geneticists who have helped spawn a mutant organism that is designed to provide the basic DNA to help fight disease throughout the world.

Labels:

Adrien Brody,

David Cronenberg,

Lars Trodson,

Sarah Polley,

Splice

Thursday, June 3, 2010

The Strange Alchemy That Made “Carnival Of Souls” Work

By Lars Trodson

The challenge in creating a believable dreamlike sequence for the movies is in getting the recipe right: a dream in a movie must have that odd mixture of fact and fiction played out on both a three-dimensional landscape and in that other place we can only call the dreamscape. This is a place beyond our dimension, although it is populated with people we know and its topography is certainly recognizable.

There is something else as well. Dreamscapes in movies almost always tend to emphasize their ephemeral qualities, their creators want them to float away, because that’s what dreams are supposed to do. That's what we think dreams do; they pop when we wake.

And yet, as we know, dreams are uncommonly sturdy, both in their logic and in their stubborn willingness to keep following us. Dreams may have more of an impact on us than our daily interactions. They are often far more durable than a conscious experience. That, too, becomes a challenge to the artist. How does one create a movie dream that feels like a dream, but also has that quotidian reality that all dreams have in their hearts?

The challenge in creating a believable dreamlike sequence for the movies is in getting the recipe right: a dream in a movie must have that odd mixture of fact and fiction played out on both a three-dimensional landscape and in that other place we can only call the dreamscape. This is a place beyond our dimension, although it is populated with people we know and its topography is certainly recognizable.

There is something else as well. Dreamscapes in movies almost always tend to emphasize their ephemeral qualities, their creators want them to float away, because that’s what dreams are supposed to do. That's what we think dreams do; they pop when we wake.

And yet, as we know, dreams are uncommonly sturdy, both in their logic and in their stubborn willingness to keep following us. Dreams may have more of an impact on us than our daily interactions. They are often far more durable than a conscious experience. That, too, becomes a challenge to the artist. How does one create a movie dream that feels like a dream, but also has that quotidian reality that all dreams have in their hearts?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)