Raymond Chandler was born on July 23, 1888.

On the 125th anniversary of his birth, we take a look at the origin of his most

iconic phrase, "mean streets." Who actually coined it, and who used

it in a story first?

By Lars

Trodson

Raymond

Chandler is almost always cited as the man who coined the phrase "mean

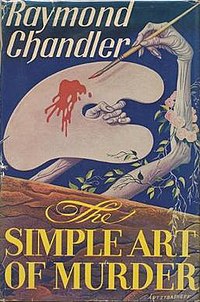

streets." His essay, "The Simple Art Of Murder," contains the

oft-repeated quote: "Down these mean streets a man must go who is

not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid." The essay first

appeared in The Atlantic Monthly in 1944 and was reprinted in an anthology in

1950 under that same title.

The Library of America, on its

page about Chandler, writes: "In his first novel, The Big Sleep (1939),

the classic private eye finds his full-fledged form as Philip Marlowe: at once

tough, independent, brash, disillusioned, and sensitive—and man of weary honor

threading his way (in Chandler's phrase) "down these mean streets"

among blackmailers, pornographers, and murderers for hire."

In an article published on June

5, 2013 in Los Angeles Magazine titled "The 10 Most Iconic Cop Shows SetIn the Mean Streets of L.A", the author writes: "'Down these mean

streets a man must go who is not himself mean...' Raymond Chandler, the patron

saint of pulp noir, once wrote."

On and on it goes. It is, in

fact, almost impossible to find an article or a blog posting that does not in

some way directly connect Chandler to the phrase "mean streets," so

pervasive is the idea that the phrase is his.

The phrase does seem so distinctly American and it's natural to apply such a muscular phrase to a writer like Chandler, who did indeed prowl back alleys in his fiction.

But another writer deserves

credit for the phrase. British author Arthur Morrison published a book called

"Tales of Mean Streets" in 1894. "Mean" didn't mean

"angry" or "dangerous," but instead indicated someone or

something that was miserly or broken down.

Morrison's book is a portrait of

the denizens of the East End of London, the location of grinding, oppressive

poverty at the time the book was published.

Chandler, who grew up in London

and was a British citizen almost to the end of his life, almost certainly was

aware of that book.

In "The Simple Art of

Murder," the essay from 1944, the detective writers Chandler most admires

are English. After mentioning a few examples of detective fiction, Chandler

says: "The ones I mentioned are all English only because the authorities

(such as they are) seem to feel the English writers had an edge in this dreary

routine, and that the Americans, (even the creator of Philo Vance – probably

the most asinine character in detective fiction) only made the Junior

Varsity."

Chandler also references The

Detection Club in this essay, which was founded in London in 1930 by a group of

esteemed mystery writers. Chandler described the group as the "Parnassus

of English writers of mystery. Its roster includes practically every important

writer of detective fiction since Conan Doyle.

Both Morrisson and detective

fiction writer H. C. Bailey were among the co-founders, so the link is made.

More about Bailey in a minute.

Morrison's book might be dated

but is not dull. It's full of brutes, drunkards, good women turned bad — all of

whom live on the south side of town.

Think of what it must have been

like for a young Raymond Chandler to have come across a paragraph such as this,

taken from the introduction, which is not only sets the tone for Chandler's own

work, but contains obvious connection to Chandler's name that must have

solidified, in his mind, a connection to this milieu:

"Of

this street there are about one hundred and fifty yards--on the same pattern

all. It is not pretty to look at. A dingy little brick house twenty feet high,

with three square holes to carry the windows, and an oblong hole to carry the

door, is not a pleasing object; and each side of this street is formed by two

or three score of such houses in a row, with one front wall in common. And the

effect is as of stables.

"Round

the corner there are a baker's, a chandler's, and a beer-shop. They are not

included in the view from any of the rectangular holes; but they are well known

to every denizen, and the chandler goes to church on Sunday and pays for his

seat."

A

"chandler" is a person who was the household head of wax and candles.

Someone who, in other words, helped shed light in dark places. It's easy to

picture a young Raymond Chandler reading this passage, and envisioning himself

that very man, the chandler, living among these people and trying to make his

way in the world.

But

after Morrison, it seems as though another British writer, H.C. Bailey, wrote

of these same "mean streets" a decade before Chandler himself used

the phrase.

Bailey

(1878 - 1961) wrote stories featuring the medical detective Reggie Fortune and

a sleuth by the name of Josiah Clunk. Bailey was highly regarded enough to have

been included in a Modern Library anthology called "Fourteen Great

Detective Stories" that was published in 1949.

Bailey’s

contribution is a story called “The Yellow Slugs," which features Reggie

Fortune, from 1935. Note the similarity between this passage and the earlier

one from Morrison, the reference to the same "dingy houses" and a

tweaked reference to mean streets:

“Two

slow miles of dingy tall houses and cheap shops slid by, with vistas of meaner

streets opening on either side. The car gathered speed across Blaney Common, an

expanse of yellow turf and bare sand, turbid pond and scrubwood, and stopped at

the pile of an old poor law hospital.”

"The

Yellow Slugs" is a tough little story that has his medical detective

Fortune (certainly a harbinger of private eyes that have names with double

meanings) investigating an incident with a young brother and sister that may or

may have not been attempted murder.

When

the mother of the two kids tries to convince the police that the incident was

accidental, Fortune has this exchange with another cop named Bell that has all

the earmarks of the style that was to become known as "hard-boiled:"

"She's been here, half off her head, poor thing," said Bell.

"She wouldn't believe the boy meant any harm. She told me he couldn't, he

was so fond of his sister. She said it must have been an accident."

"Quite natural and motherly. Yes. But not adequate. Because it

wasn't an accident, whatever it was. We'd better go and see the mother."

"If you like," Bell grunted reluctantly.

"I don't like," Reggie mumbled. "I don't like anything/

I'm not here to do what I like." And they went.

The

next sentence is this:

"People were

drifting home from the common. The mean streets of Blaney had already grown

common in the sultry gloom."

There

are no mean streets in Chandler's first published story, "Blackmailers

Don't Shoot," from 1933, just assorted unsavory characters who are trying

to outshoot or outsmart the other guy. There are cigarettes and hard faces, and

Chandler, writing fiction for the first time, seems to have emerged

fully-formed. This is a story where a guy named Mallory is trying to blackmail

a movie star over some sexually explicit letters he has come across — a plot

device in countless imitations. Chandler also tosses off a phrase that would

pop up elsewhere.

When

the cops are trying to strong-arm some information out of Mallory, one of the

cops says: "Maybe you better talk, bright boy."

Anybody

who has read one of Ernest Hemingway's most famous Nick Adams short stories,

"The Killers," will remember the exchange in the diner when the two

assassins come to town to kill the Swede. In the exchange with George, the

owner of the diner, about what's on the menu for dinner, the killers say:

"You're a pretty bright boy, aren't

you?"

"Sure."

"Well, you're not," said the other

little man. "Is he, Al?"

"He's dumb," said Al. He turned to

Nick. "What's your name?"

"Adams."

"Another bright boy," Al said.

"Ain't he a bright boy, Max?"

So

Chandler made his mark from the beginning, which is an astonishing achievement

for any writer.

The

phrase "mean streets" is now more commonly associated with the Martin

Scorsese movie from 1973 (the title of which may have been inspired by a memoir

written in 1967 titled "Down These Mean Streets," by Piri Thomas

about his life of crime in Spanish Harlem) than it is with the noir writing of

the 1930s and 40s. Chandler himself may now be an anachronism. Philip Marlowe

has been replaced by Jason Bourne and even a testosterone-driven Sherlock

Holmes. No one throws punches any more, let alone lights up a cigarette.

But

on the 125th anniversary of his death, it's good to remember that even if

Chandler didn't create these mean streets, he sure did populate them more

colorfully and more vividly than any writer before or since.