By Lars Trodson

The thing that was going through my mind as I watched Jim Carrey’s version of “A Christmas Carol” when it was in theaters a few years back was whether that movie was finally going to put an end to any new filmed versions of the book. That 3D spectacle (produced by Disney) seemed so tired and spent, so devoid of any new ideas (I wondered if the screenwriters had actually read the book), that I thought it was the final nail in Jacob Marley. This turned out to be true. The versions that have come out in the four years since have been jokey, gimmicky, low-budget jobs (one has a character named Bob Crotchrot instead of Bob Cratchit, to give you an idea.)

But

truth be told, the entire "Christmas Carol" franchise had already

seemed to have grown damp and tired by 2009. The story had been repeated so

many times, in so many way, that it no longer had any real power to surprise or

delight. The novel is so slender that a 90 minute or two hour version pretty

much contains everything that Dickens wrote. Even the classic half-hour version

by Richard Williams from 1971 feels, in its own way, complete.

I think

watching “A Christmas Carol” has become the tradition. We don't really

have a transformative experience watching the story any more. We go through the

motions; the viewing of the movie is now a bauble, an ornament, a connection to

our past yuletide traditions. Scrooge opens his window and calls out to the boy

("A wonderful boy! An intelligent boy!") but it no longer moves us.

Scrooge

is, simply put, too familiar, too famous. One of the reasons for this is that

the novel is in the public domain; you don’t have to pay any rights for it. If

you’re an actor of a certain age (Patrick Stewart, Michael Caine), or a

production company looking to add to the pile of holiday fare, you can produce

your own version. More than one local theater company balances its books at the

end of the year by putting on a production of "A Christmas Carol."

It’s too

bad that it's run out of steam, because it is a lovely story. The characters

are beautifully drawn — and of course Scrooge himself is a masterful creation.

He’s obviously one of the great creations in all of literature. I've begun to

wonder if there was any life in the old boy yet. There may be, if you think of Scrooge as someone who has not simply rejected the world around him, but more importantly as someone who may have been hurt by the world, both as a boy and as a man, and who decided to turn away from it. He's not mean, he's simply a person who decided to protect himself by encrusting himself with the kind of nastiness that will ensure no one will ever get close. But why?

I've

been looking at various versions, almost all of which have remarkably similar

beginnings. It’s usually a London street scene, bustling, people singing

carols, and the camera soon swings into Scrooge & Marley’s. Scrooge is

counting his money and Bob Cratchit is trying to warm himself by the heat off a

single lump of coal.

Then in

comes Fred, Scrooge's nephew, an affable fellow, and then the two men from the

charities ask Scrooge to help out the less fortunate come into the office. Even

the most casual acquaintance of this story can repeat this dialogue: "If

they would rather die, they had better do it, and decrease the surplus

population." After they are rebuffed, Scrooge debates Bob Cratchit about

the merits of the holiday — "A poor excuse for picking a man's pocket

every twenty-fifth of December!" — Scrooge goes home and he’s visited by

Jacob Marley's ghost, who laments that he neglected his fellow man. He tells

Scrooge that he may "have yet a chance and hope of escaping my fate. A

chance and hope of my procuring, Ebenezer."

To

which Scrooge replies: ""You were always a good friend to me."

There it is. It

seems that the friendship between Scrooge and Marley is one element not fully

explored in the filmed versions of the story. I'm not going to associate this

relationship with kind of homoerotic undertones — although some have tried —

but the beginning of the book is, after all:

“Marley was dead, to begin with." But the reference is most often

used as a mechanism so that we know who Marley is when his ghost comes to pay a

visit a later on.

Scrooge was really devastated by

Marley's death. Dickens puts it this way: "Scrooge and he were partners

for I don't know how many years. Scrooge was his sole executor, his sole

administrator, his sole assign, his sole residuary legatee, his sole friend,

and sole mourner."

Those last two descriptions are key: each was the other's only friend.

There

is another pointed detail: "Scrooge never painted out old Marley's name.

There it stood, years afterward, above the warehouse door: Scrooge &

Marley. The firm was known as Scrooge & Marley. Sometimes people new to the

business called Scrooge Scrooge, and sometimes Marley, but he answered to both

names. It was all the same to him."

Having

lost his friend, having lost the affection of his sister and his first and only

love, Scrooge has simply shriveled up, and so it is not out of callousness that

he ignores Bob Cratchit and Fred, it is out of hurt and jealousy. It is the

fact that they have happy families, and children, and company — and Scrooge

does not (the cruelty of Scrooge's father is hinted at). It could also be why Scrooge

was lonely as a child, and the loneliness of children is a motif throughout the

story.

At one

point, in a moment that does not make it from book to screen, the Ghost of

Christmas past asks:

"What is the matter?"

"Nothing,"

said Scrooge. "Nothing. There was a boy singing a Christmas carol at my

door last night. I should like to have given him something; that's all."

Some of

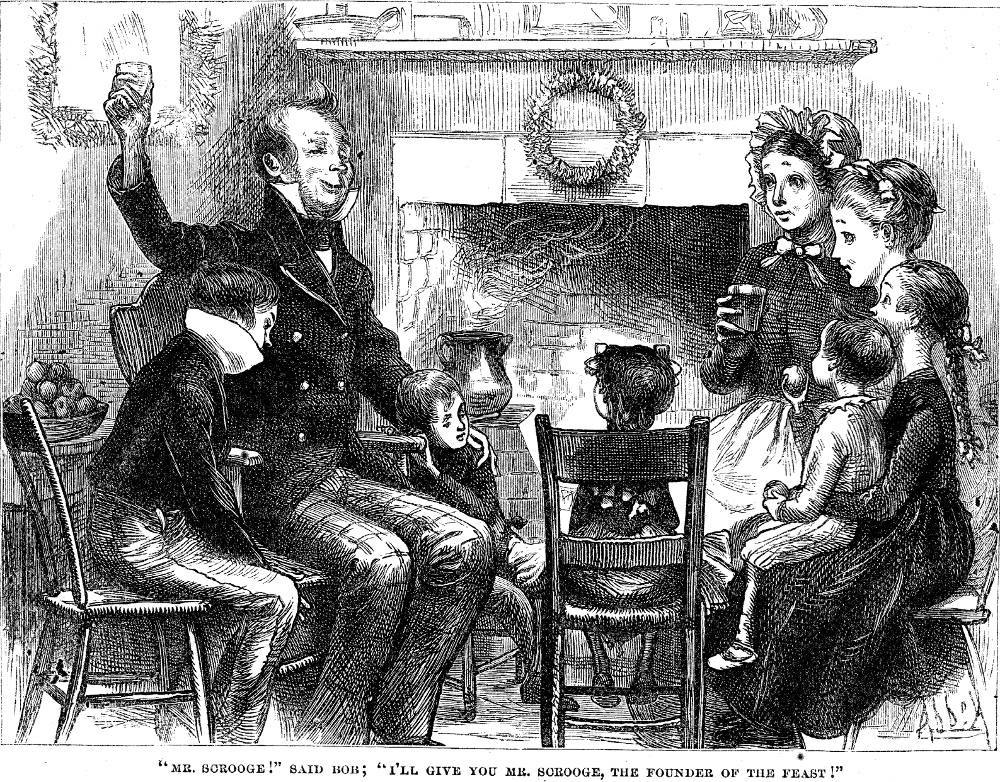

the warmest and heartbreaking moments in the book occur in the Cratchits'

rooms, around the table, with Tiny Tim and without him.

Of

course, the Ghost of Christmas Present shows Scrooge the images of Ignorance

and Want in the guise of two starving, filthy children, a boy and a girl.

Take

this exchange, not often included in any filmed version, between Scrooge and the Ghost

of Christmas Past. They are talking about Scrooge's sister, Little Fan:

"Always a delicate creature, whom a

breath might have withered," said the ghost. "But she had a large

heart!"

"So she had," cried Scrooge.

"You're right. I will not gainsay it, spirit. God forbid!"

"She died a woman," said the ghost,

"and had, as I think, children."

"One child," Scrooge returned.

"True," said the ghost. "Your

nephew!"

Scrooge seemed uneasy in his mind, and

answered, briefly, "Yes."

And, of

course, the first person Scrooge sees on the morning of his redemption is a

young boy, who goes and buys the fatted goose for the Cratchits.

Scroggie was Scottish (Dickens saw the grave in Edinburgh). A popular stereotype of the Scots is that they are impecunious and that is of course one of Scrooge's dominant traits.

The other element to explore is the idea that Scrooge is a true outsider; that is, he may not be a Londoner, and perhaps not even an Englishman. His outsider status may have a geographic reason.

I had looked at an online version of Dickens' biography and read that the author had seen a grave of a Scotsman named Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie, and the inscription on the headstone was "A Meal Man" — meaning he sold corn. Dickens, so the story goes, misread the words as "A mean man", and was left with the sad impression that Scroggie must have been truly mean to be burdened with this description for all eternity.

Scroggie was Scottish (Dickens saw the grave in Edinburgh). A popular stereotype of the Scots is that they are impecunious and that is of course one of Scrooge's dominant traits.

It would not have been unusual for Dickens (or any other 19th century novelist) to engage in some casual bigotry and ascribe a popular stereotype, yet, it's important to note that Dickens doesn't mention what nationality Scrooge is. All we know is that he lives and works in London. But it would not be historically inaccurate to have a Scotsman living in London in 1843, the year the book was published.

By 1860 (according to oldbaileyonline.com), there were 3.2 million people in London, and "38 percent of those folks were from someplace else."

Having Scrooge be Scot would add to his alienation. He would be outside of London society — while his nephew Fred would be much more assimilated and much more comfortable. It could be (if you wanted to add to the backstory, that Scroggie changed his name to Scrooge to blend in but to also not completely erase his heritage. (In color versions of "A Christmas Carol", including the George C. Scott and Mr. Magoo versions, the youthful Scrooge has red hair, a decidedly Scottish trait, so this connection is at least hinted at.)

But why not make it more explicit? Why not employ an actor that is decidedly Scottish to play the role? (It should be pointed out that Alistair Sim, the actor most associated with Scrooge, was, indeed, Scottish, but there's no trace of a burr in his accent.)

It

seems as though there are rich veins to be mined in "A Christmas

Carol" if the themes of friendship and family are explored more

personally, more from Scrooge's point of view, rather than simply painting him

as a mean, cheap, heartless old man. It could be that his story will resonate

more powerfully if we realize that Scrooge has been as much rejected and hurt

by the world, as he has been by it.

In that

way, I've written what I think might be an affecting way to open the story:

SCENE 1

SFX: The sound of a clock ticking

can be heard before any image is seen.

WORDS ON THE SCREEN: New Year's

Day, 1838

FADE IN: The point of a dip pen

hovers over a document in extreme closeup.

CUT TO: A line on the document

where a signature should be written.

CU: A drop of black ink drops

just above the line and splashes on the paper.

CUT TO: The point of the pen is

set down just above the line, and the hand slowly, neatly, writes out the name:

EBENEZER SCROOGE.

A solicitor picks up the

document, looks at the signature, and blows on the ink to dry it. He places the

document in a folder, and he places the folder in his valise.

CUT TO: SCROOGE, sitting still and

staring at nothing in particular.

SOLICITOR

(Gently)

Mr. Scrooge?

SCROOGE looks up, silently.

SOLICITOR

Our business is concluded, Mr. Scrooge.

SCROOGE nods but does not move. The SOLICITOR

puts on his coat.

SOLICITOR

(Picking up his hat)

Mr. Scrooge?

(Silence)

Will you be moving into Mr. Marley’s lodgings?

SCROOGE

What?

SOLICITOR

Mr. Marley has left you his lodgings. Do you

have any plans for them, sir?

SCROOGE

(Quietly)

I suppose I’ll be moving into them, yes. I

don’t know. Perhaps.

SCROOGE stands.

SOLICITOR

(Helping SCROOGE on with his coat)

You were his only friend, Mr. Scrooge?

SCROOGE

He was my

only friend, yes.

SOLICITOR

(brushing Scrooge’s coat)

A horrible thing to have happen on Christmas

Eve, sir.

SCROOGE

Excuse me?

SOLICITOR

Mr. Marley's death, sir.

SCROOGE

Oh, yes... well.

SOLICITOR

Well, a good new year's day to you, sir.

SCROOGE

Oh, yes. Thank you.

SOLICITOR

Will you be quite all right, sir?

The SOLICITOR picks up his valise and puts on

his hat. SCROOGE puts on his hat and walks to the door.

SOLICITOR

Health and happiness, sir.

SCROOGE turns and looks at the SOLICITOR with a

mixture of anger and sadness and he makes a noise, more like a grunt, to

acknowledge the absurdity of the SOLICITOR's comment.

SCROOGE walks out the door and into the wind

and the cold.

OPENING CREDITS

.jpg/220px-A_Christmas_Carol_(1971_film).jpg)